"That's three strikes, run for your life"

The Department of Justice announced charges against two people associated with a network of violent white supremacist channels on the messaging app Telegram known as "Terrorgram" today.

Dallas Erin Humber, 34, and Matthew Robert Allison, 37, face 15 counts for their involvement in the network, including soliciting hate crimes, soliciting the murder of federal officials, and conspiring to provide material support to terrorists. The pair, per the DOJ, could each face up to 220 years in prison. In a 37-page indictment, U.S. officials describe Humber and Allison as ringleaders in the Terrorgram network and accuse them of using it to encourage attacks on prominent politicians, infrastructure, and minorities.

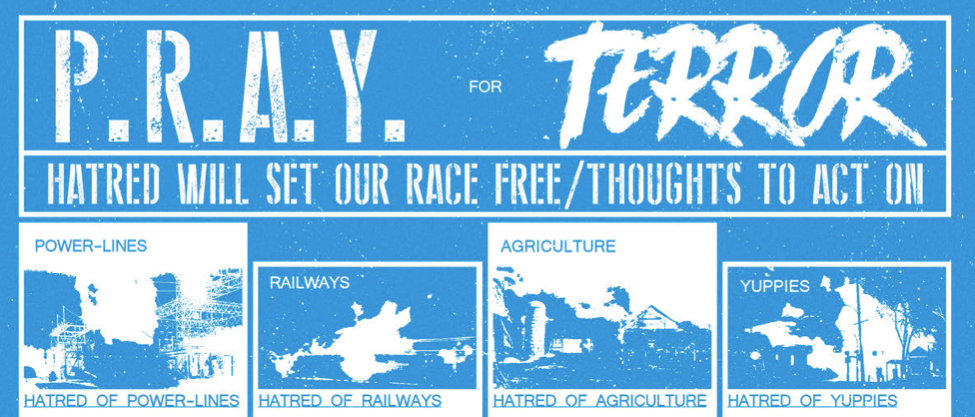

The indictment refers to multiple Terrorgram publications, including a 250-plus page document called "The Hard Reset"; a documentary called "White Terror"" that celebrates over 100 acts of white supremacist violence; and "The List," a collection of public officials and leaders to be targeted with violence up to and including assassination. In it, prosecutors spend a great deal of time on the concept of "saints," the term that Terrorgram uses to refer to white supremacist mass murderers, such as Dylann Roof, Timothy McVeigh, and Anders Breivik.

For the past several years, the Terrorgram network, or "Terrorgram Collective" as some of its followers call it, has served as a hub for an increasingly decentralized wing of the white power movement that embraces a tactic known as "accelerationism." White power accelerationists seek to usher in the collapse of the supposedly anti-white "System" through violence and other means, including attacks on infrastructure, with the hope that doing so will usher in a national socialist state. In contrast to white nationalist and neo-Nazi groups that use more traditional political methods to bring about their goals, white power accelerationists argue that "there is no political solution."

There have been neo-Nazi and white nationalist groups that embrace accelerationism as a tactic, including Atomwaffen Division and the Base, though both structured themselves more as networks for localized cells. (To put it another way, no one from Atomwaffen Division tried to register it as a 501(c)3 to my knowledge.) A slew of arrests and a growing interest from federal officials has stymied their activities. In contrast, Terrorgram-affiliated content creators saw even this level of organization as a hazard after a certain point.

"If it's got a logo, a name, and an online presence, that's three strikes, run for your life," wrote Pavol Beňadik, who used the handle "Slovakbro" online, in a post shared on Telegram in August 2020. "Having a public face does not benefit the group's members, on the contrary, it inconveniences them greatly, especially because it enables the System's troops — auxiliary AND regular — to monitor their activity much more easily."

There's two aspects of Terrorgram, which I have monitored for the better part of five years, that the indictment doesn't get into that I want to address. First, how Terrorgram has changed over time. Second, what these arrests say about the assertion that the United States needs stronger domestic terrorism legislation to combat violent white supremacists.

Spoiler: Terrorgram isn't quite what it used to be

Prior to the indictment, there's been a handful of news stories in Bloomberg and ProPublica describing Telegram, and specifically Terrorgram within it, as driving a new wave of white supremacist attacks.

The indictment nods to this characterization. It cites the perpetrator of a 2022 shooting at a LGBTQ+ bar in Slovakia, who cited Terrorgram publications in his screed; an American who was arrested in July 2024 for allegedly plotting an attack on energy facilities in New Jersey and who was in chats with Humber; and a man who shared Terrorgram content on social media prior to livestreaming himself stabbing people outside of a mosque in Turkey in mid-August.

What neither the indictment nor recent news stories capture is how Terrorgram has changed in response to moderation from Telegram, as well as bans on Apple and Google devices. In the case of moderation from Telegram itself, I'm referring to the app just outright banning channels for violating its terms of service. In terms of app bans, I'm referring to Apple and Google banning users using the official version of Telegram from their respective app stores from accessing certain channels. In the latter case, it doesn't mean that the channel is gone from Telegram per se; rather, you just need to use a different version of the app to access it.

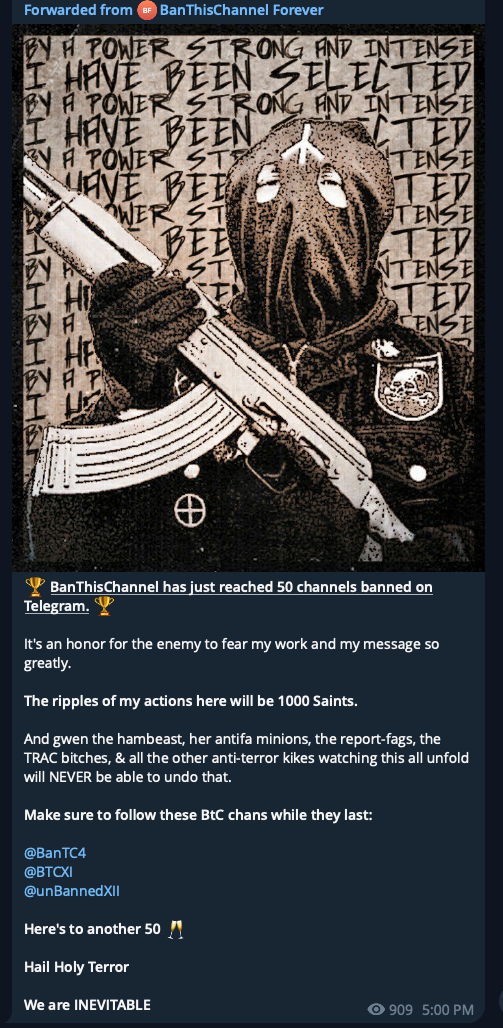

Since 2019, Telegram, as well as Apple and Google, have banned some of the core channels associated with Terrorgram dozens upon dozens of times. Channel moderators are well aware of this, so they regularly get into the practice of setting up backup channels and promote each other's content when their associates are inevitably banned. On the extreme end of evading platform bans, I found this old post from "Ban This Channel" — apparently run by Allison — from 2021. Allison, or someone else with access to the channel, claimed to have been banned 50 times. (I have no way of verifying this exact number, admittedly.)

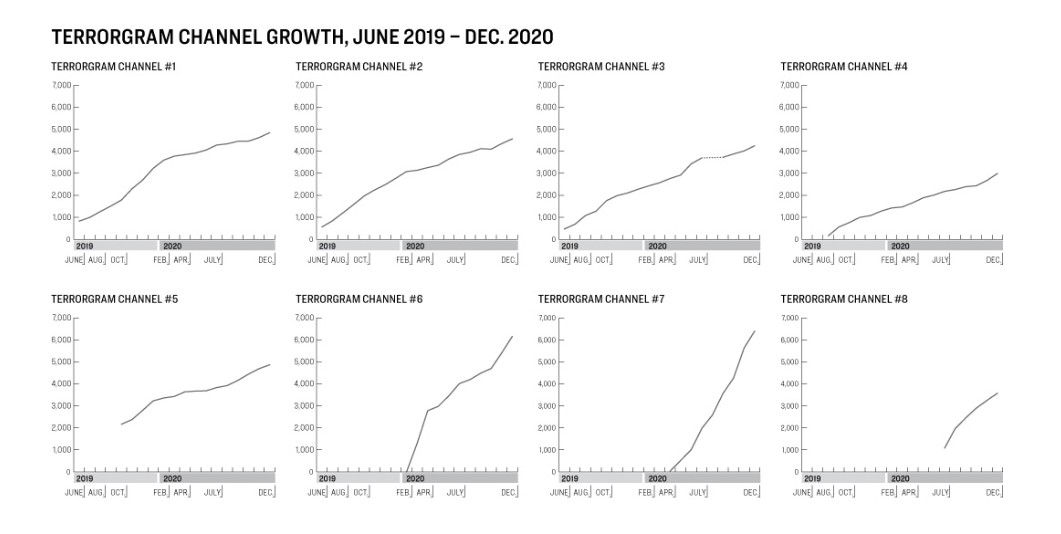

For a time, platform and app bans did little to halt Terrorgram's growth. In early 2021, my colleague Megan Squire and I published analysis showing how several Terrorgram channels had grown over time despite periodic bans.

But as bans became more aggressive over time, including after the Jan. 6 insurrection, the network's popularity slowed. By the time my colleague Jason Wilson and I reported this story on Atomwaffen Division co-founder Brandon Russell participating in Terrorgram-aligned chats, the network had come to increasingly rely on private chats that weren't open to non-members viewing them. Russell's arrest in early 2023 hurt the network even further.

That's not to say that Terrorgram's influence in terms of real-world activity has evaporated. Content and publications associated with the network and created by people like Humber and Allison are still shared on the platform today. But the level of centralization that existed in 2019 is gone.

The domestic terrorism question

One of the charges that Humber and Allison face is conspiring to provide material support to terrorists. The indictment cites a statute prohibiting people from providing "material support or resources" with the knowledge that these would be used to commit various specific crimes. In the case of Humber and Allison, these include arson or bombing federal property; arson or bombing property that is used in interstate or foreign commerce; killing or attempting to kill a federal official; and the destruction or damage of an energy facility.

It's a different statute than the one prohibiting material support to foreign terrorist organizations. Following some post-"war on terror" adaptions, that statute has been described by critics as empowering "prosecutors to prosecute conduct that might seem otherwise innocuous — translating books and publishing them online, or storing ponchos and socks."

For years, some federal officials have argued that there is a need for implementing domestic terrorism legislation mirroring that which governed the "war on terror" for so many years. (As I've argued on multiple occasions, this is a horrible idea.) These efforts, which included a discussion of naming Atomwaffen Division a foreign terrorist organization (FTO) back in 2020, fell through for a variety of reasons. But, as journalist Ali Winston pointed out on Twitter (i.e., the app that I refuse to call "X"), it seems that the DOJ found a way here of elevating charges for what would typically be considered domestic terrorism to be international. Terrorgram isn't a FTO, but the UK banned it in April.

It's an open question of what this means for the future. Federal prosecutors involved in Brandon Russell's upcoming trial agreed to met with a judge to discuss whether the government used material gathered using Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, according to The Baltimore Banner. His case will involve evidence and testimony centered around Terrorgram.