"don't let them find you": the U.S. comes for terrorgram

The U.S. government has designated the Terrorgram Collective, a loose-knit network of neo-Nazi channels on Telegram, and three of its overseas affiliates as a terrorist group, citing its ties to the perpetrators of multiple violent attacks and plots.

In a statement released on Monday, the State Department announced it had named Terrorgram Collective “leaders” Ciro Daniel Amorim Ferreira of Brazil, Noah Licul of Croatia, and Hendrik-Wahl Muller of South Africa, Specially Designated Global Terrorists (SDGTs).

The announcement did not describe Ferreira or Muller’s roles in the movement other than as channel administrators. Licul, whom officials described as “a senior member of Terrorgram,” appears to have previously been active in chats in late 2019 and early 2020 associated with Feuerkreig Division, a neo-Nazi group previously active in Europe and the United States. Journalists and antifascist activists identified Licul, then a teenager, as active in these chats under the username “buntovnik.” Under that handle, he described meeting with members of Feuerkreig Division’s cell in Croatia, claimed credit for vandalizing a World War II memorial with neo-Nazi graffiti, and discussed possible targets for attacks in the country. He also repeatedly interacted with the group’s 13-year-old leader.

“There are plans for burning down a Jewish institution in croatia though[.] There are actually a few organisations working on the plans,” “buntovnik” wrote in January 2020, according to reporting from Unicorn Riot. He left the chat after saying law enforcement visited his house later that same month.

While the announcement named Ferreira, Licul, and Muller as “leaders,” the Terrorgram Collective isn’t exactly an organization in the traditional sense of the word. As I and others have noted, white supremacists started the collective partially in response to some of the pitfalls they saw with more traditional white supremacist groups. It has affiliates in the United States, Europe, South America, and — apparently — Africa and has inspired acts of violence across a similarly broad geographic spectrum.

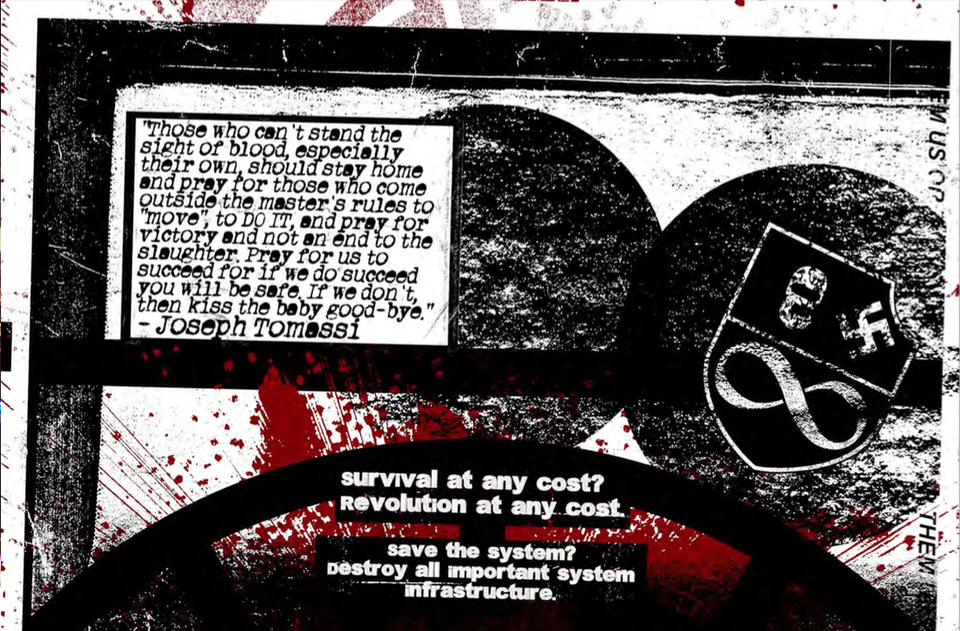

“If it’s got a logo, a name, and an online presence, that's three strikes, run for your life,” wrote Pavol Beňadik, a Terrorgram affiliate who used the handle “Slovakbro”, in a Telegram post from August 2020. Or, from Terrorgram publication "Do It for the 'Gram": "No names, no logos, no websites, no emails, no brands — that way lies movementarianism, division, petty infighting and paranoia." Instead of holding membership lists, organizing meetups, and participating in demonstrations, Terrorgram affiliates encouraged each other to plan attacks on infrastructure, as well as minorities, politicians, journalists, and activists. It uses its network to release publications—it has published four so far—and distribute them.

The effort is the culmination of several years of various lawmakers, nongovernmental organizations, and other interested parties lobbying the federal government to combat white supremacist violence as terrorism. And as we go into the second Trump era, it also raises the possibly uncomfortable question: What next?

Bringing the “war on terror” home… again

The decision to formally name the Terrorgram Collective and some of its affiliates as terrorist appears to date back to a discussion within policymaking and anti-extremist circles in late 2019 and early 2020 over whether to apply a similar designation to Atomwaffen Division, a now-defunct neo-Nazi group founded in Florida.

Following the violence at the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally and a rash of mass shootings by white supremacists in the United States and abroad in 2019, some anti-extremist think tanks, nonprofits, and lawmakers began lobbying for the United States government terrorist designations to white supremacist groups. The United States has several mechanisms through which to regulate and criminalize activity with legally proscribed terrorist entities. These include Foreign Terrorist Organizations, or FTOs, which allows the U.S. government to prosecute anyone who provides “material support or resources” to these groups.

The State Department, which keeps a list of groups identified as FTOs, also has the power to name organizations as Specially Designated Global Terrorist, or SDGTs. This designation allows the government to impose financial sanctions, but limits its capacity to prosecute members to the same extent under the material support statute.

In March 2020, someone tipped off Politico that State Department officials were pushing to designate Atomwaffen Division — again, a group founded in Florida, which, last I checked, is still part of the United States — as a Foreign Terrorist Organization. While the word “Florida” does not appear in the article, a sentence explaining“the existence of Atomwaffen was first announced in October 2015 on a now-defunct online forum called Iron March, which was founded out of Russia,” does. (This is admittedly true, but it does a number on muddling Atomwaffen’s very domestic origins in FLORIDA, nevertheless.) In response to these rumors, James Mason—the author of the terrorist tome Siege who worked closely with Atomwaffen Division leadership—announced the group was disbanding.

Look, I’m not a white supremacist or a lawyer, but I would add that it probably did not help Atomwaffen’s case that around this same time, I and others observed small cells using the group’s name and logo active in Russia and Germany.

The State Department ultimately declined to name the Florida-founded Atomwaffen Division a Foreign Terrorist Organization and instead leveled sanctions against another group called the Russian Imperial Movement. RIM promotes antisemitic conspiracies and members of its paramilitary arm have fought in eastern Ukraine among pro-Russian forces, in addition to providing training to and/or networking with European and American neo-Nazis.

U.S. government officials have continued to express concerns about the threat posed to white supremacist terrorism, including to infrastructure. In July, the State Department named the Nordic Resistance Movement an SDGT, citing attacks that two of its members carried out in 2017.

The decision to designate Terrorgram an SDGT also follows a series of bans and arrests specifically targeting the network in the United States and abroad. The United Kingdom added Terrorgram to its list of proscribed terrorist organizations in May. In September, Department of Justice officials arrested and charged two U.S.-based administrators associated with Terrorgram, Dallas Erin Humber and Matthew Robert Allison on 15 counts, including soliciting the murder of federal officials and conspiring to provide material support to terrorists.

What next?

Writing in July 2020, academic Anna Meier noted that the impact of these designations are not always direct.

“Designation may combat political violence in some circumstances, but its largest effects lie elsewhere,” Meier wrote in Lawfare. “In particular, designation signals what kinds of political contention are unacceptable to the U.S. government—and preserves this categorization as much as possible as public sentiment shifts.”

The same, I think, could be said of types of extremism. Under Trump’s prior administration, his Department of Justice officials went after groups like Atomwaffen Division, The Base, Feuerkreig Division, and other violent white supremacists. Yet he ended his term with a spectacular display of political violence that the mainstream right has come to embrace. And he promises to start his one with a round of pardons for at least some individuals convicted of charges related to the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection.

“Most likely, I’ll do it very quickly,” Trump recently said on NBC’s “Meet the Press.” “Those people have suffered long and hard. And there may be some exceptions to it. I have to look. But, you know, if somebody was radical, crazy.”

Determining what the forthcoming Trump administration means for these sorts of investigations and prosecutions into white supremacist violence is impossible at this point. But what it does make clear is just how muddled the divide between “acceptable” and “unacceptable” political violence, including from different segments of the extreme right, is about to become.